With most people at work five days a week, many are unable to see the “hidden world” which caregivers operate in, or the lack of social and financial support provided to them.

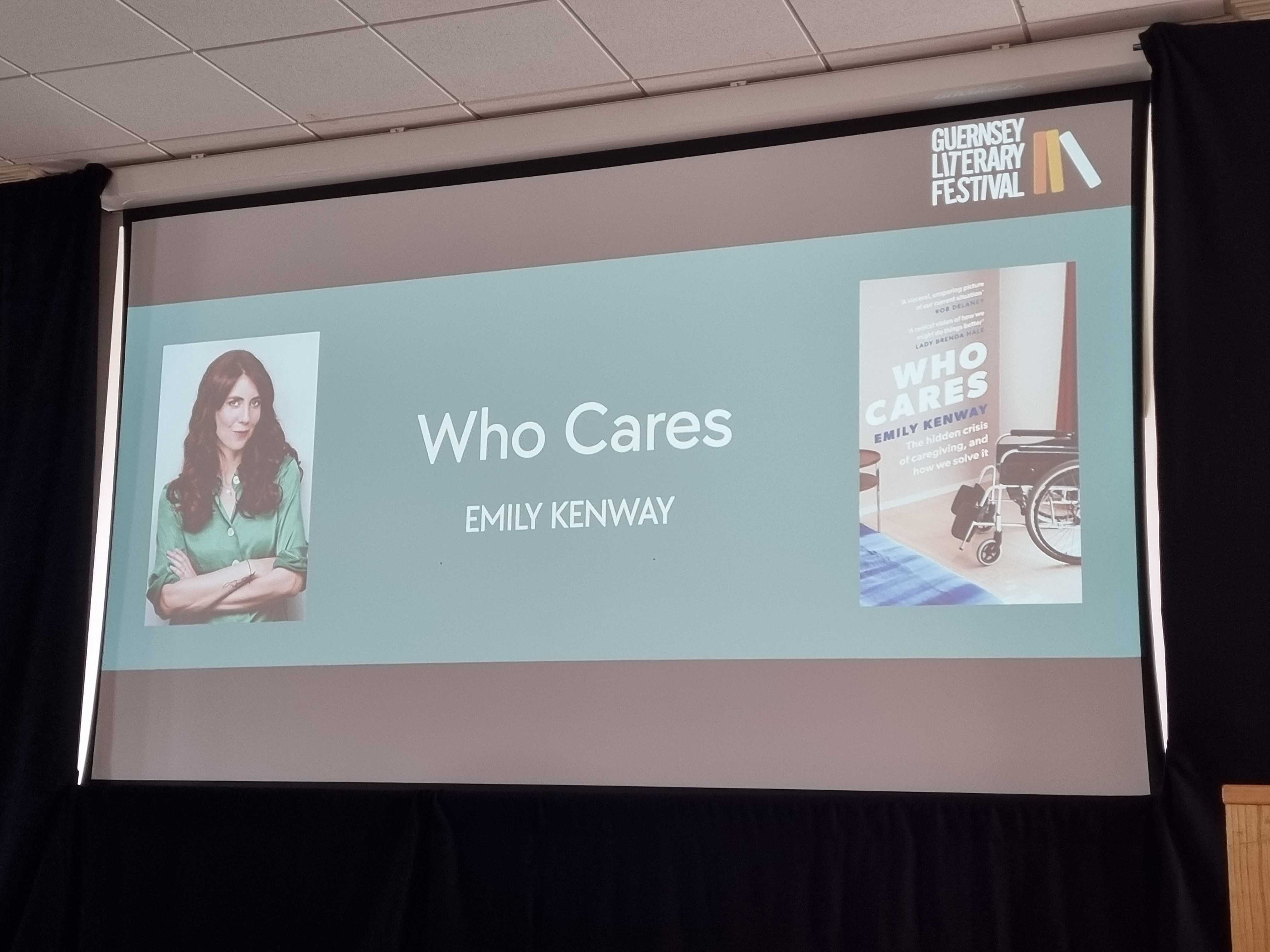

Social researcher and writer Emily Kenway was interviewed by Susie Gallienne, a children’s charity worker, at the Guernsey Literary Festival yesterday for her new book ‘Who Cares: The Hidden Crisis of Caregiving, and How We Solve It’.

Ms Kenway was working a “high pressure” job in London when she began looking after her terminally ill mother, slowly reducing her hours as the demands of caring intensified.

Sometimes she had no time to look after herself by cooking “proper meals”. On the Tube one day, she collapsed due to exhaustion. A lie in when feeling sick was also off the table as caring became all-encompassing. Brain zaps became common: “I basically broke."

Her employer was understanding but encounters with colleagues could be challenging. She said, “unless there was an extreme,” such as a fall or a major hospital visit, “it wasn’t talked about”.

Those plunged into caregiving roles must also battle with limited time for leisure, and the threat of losing their jobs since there is little to nothing for carers in employment contracts.

Ms Kenway said she coped with the stress of her new responsibilities by writing, initially in diary form. As she delved deeper into the role and heard wider experiences through online carers’ networks, she decided it needed to be a book.

These conversations were held weekly through Zoom since, as Ms Kenway put it, “most people who are caring can’t wander off in the middle of the day”.

Pictured: Ms Kenway spoke at Les Cotils on Sunday afternoon.

The social research on care finds it is heavily skewed towards women; both those providing the care each day, and those with first-hand experience of the practice.

Ms Kenway interviewed dozens of professionals and volunteers globally to gather a broad view of different systems and perspectives.

The trends were clear. Carers are more likely to be worse off. In the UK, they are more likely to use food banks, while in India they are “likely starving”.

It also common that the sick will refuse or deny care, which Ms Kenway argues is missing from the “political narrative”, and a dwindling supply of carers is since “everyone is at work”.

Pictured: The States of Guernsey rejected an attempt to increase carer's allowance last year.

“Care is psychologically difficult… there’s no cultural way to talk about that,” she said, such as her situation where the parent/child role was switched.

“I felt I had become a parent without any say in the matter… people don’t get it unless they’ve done it."

She hopes her work will help to illuminate the realities of caring for those without experience, but also to assist caregivers themselves.

“Putting your own needs first is very difficult for carers,” she said. “How do you not feel guilty for putting yourself first?”

She admitted that had her mother lived longer she wouldn’t have been able to continue alone. That was because “those who do care will be very, very poor in their old age”.

Because of that, she questioned why there is a “discrepancy between parental leave and carers allowance”.

Her starting action point was” “if carers are essential, how do you change the world around it?” Her suggestion is ensuring job security, while providing “long paid breaks” to allow the necessary care to occur.

The practical and tangible elements of care, like going to the shop, and organising medical appointments, will demonstrate the value in stewarding caregiving, and allow slack to be provided for those purposes, she argued.

Pictured: Robotic assistants are being rolled out to take on some care responsibilities.

Looking forwards, Ms Kenway said technological advancements are now on the market, but she cast doubt over whether it would be a “silver bullet” to the care question.

Artificially intelligent “social robots” are already being used in Japan – billed as companions and assistance devices – to remind users to take medication, listen to music, and to ask how they are.

The UK is also developing “trustworthy machines” to help wash people and collect objects around the home.

But Ms Kenway wondered why these machines have become necessary, and whether it would be a palatable reality for those requiring care.

“It’s not just that there are more elderly people, no-one is allowed to be paid or give time to caring.

“If it’s all robots, it might just be you sitting in a room.”

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.