Economic arguments for investing in health like keeping people in work are becoming as important as those about supporting individuals, it has been argued.

The Health Improvement Commission hosted a conference about the power of prevention and partnership in creating a healthier future as policy makers continue to grapple with the rising cost of healthcare.

It comes against a backdrop of people living in ill-health for longer, a trend that can be exacerbated by your circumstances, for example if you are impacted by deprivation.

In the UK, those living in the least deprived areas can expect to live until 70 to 70.1 years without having any limiting long term conditions, but for those in the most deprived areas it is just over 50.

"Conditions such as musculoskeletal conditions, lower back pain, knee pain, inability to move, and to be mobile, are some of the most common causes of poor health reported by individuals," said Professor Kevin Fenton, President of the Faculty of Public Health.

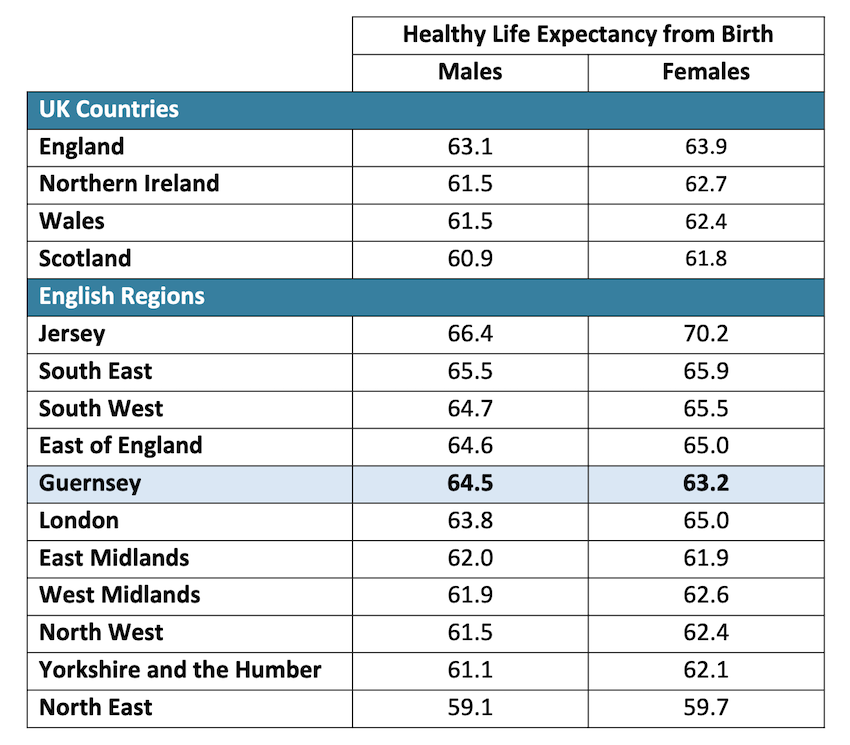

Pictured: Comparison of healthy life expectancy at birth between Guernsey (2019–21), Jersey (2016–18), UK Countries and English Regions (2018–20).

"We also know that mental health conditions, anxiety and depressive disorders are also driving the poor health that people report. And then you combine that with other long term conditions such as heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and other chronic diseases. These are forming part of what drives people from good health into poor health, and then create some of the pressures that we're seeing on health and care systems."

Inequalities are widening and that can be analysed through different factors, like ethnic and racial differences, by gender, age, or living in urban versus rural areas.

"When we look at these data for differences across any group, we must look beyond the data to look deeper to understand why are these inequalities occurring? And how are we going to be addressing them as well?"

He made the case for broadening the argument that this matters not just to individuals and communities, but also to the success of society.

"We are in a place and in a phase, where creating the economic arguments for investing in health are becoming as important as the arguments to support individuals and communities."

Pictured: Professor Kevin Fenton at the Health Improvement Commission conference.

Addressing mental health and musculoskeletal health are key issues. They are the most common reasons why people are falling out of the workforce and thereby affecting economic productivity in a society."

Creating environments for health are important.

"If we're an environment where the markets and commercial determinants of health are allowing poor food, tobacco, cheap alcohol to be in our society, then that accelerates all of the findings and features that we've been discussing so far. So from an economic perspective, the public health argument now is becoming critical."

Public health was essential to the economic sustainability of society, he said.

He argued for new narratives when talking about health.

"We know that poor health is having a significant impact on the economy," he said.

"We need new narratives which talk about the aging population, the proportion of the working age population that is falling out of work because of poor health.

"So we need to be absolutely clear about what we are recommending as public health people, and what we know works, improves health, and how that can be part of the solution as well.

"And we need to bring our public health skills of data, of partnerships, of policy development, of working with communities to become part of this solution as well, just as we did, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, when we stood up, and we were a part of helping the nation to meet this acute, once in a generation challenge.

"I would argue that our call now is to help take part of this narrative and hopefully, improve and address the economic challenges that we face."

Factors driving poor health are preventable.

"In fact, we know that nearly 42%, nearly half of all our ill health and early deaths are linked to potentially preventable risk factors. And when we look at these risk factors, we see factors such as diet, high blood pressure, tobacco, and alcohol, are the major behavioral risk factors."

This confirms why HIC is focusing exactly on these issues as core priorities for its work.

"We need to ask ourselves, are we missing opportunities to accelerate our prevention interventions?"

Prevention works and when asked the public wants to see more done on this, he said.

"We want clean water, we want streets which are walkable, we want parks which are safe, we want access to green spaces, we want to ensure that we've supported to live healthier lives. So from a policy perspective now that the public is with us. From an evidence perspective, we know that we have a prevention toolkit that works."

He spoke about how effective tackling the availability of cheap alcohol through minimum unit pricing had been in Scotland, for example, in reducing hospital admissions and deaths.

Smoking bans and interventions had reduced heart attacks and child asthma in the UK over time.

"Prevention requires us to be comprehensive and multilevel. In other words, it must require individual community and societal interventions working concurrently and consistently over time to have its impact. Prevention can be cheap, but it can be even more effective if it is invested in to have those prevention interventions at scale.

"It makes no sense to have a cervical screening program only covering 30% of the population. It makes no sense having childhood vaccines, which are only covering 50% of the population."

There would always be trade offs and tough choices, but public health needed to work with policymakers to prioritise, he said.

"We need to become slicker in understanding not only the lives saved, but money saved as well and the return on investment."

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.