An independent review of Guernsey's justice framework concluded that there is no over-arching strategy defining what the island's sentencing regime is trying to achieve and why. In light of an appeal against the island's drug laws, Express re-visited the report's findings and probed whether Guernsey's "piecemeal" sentencing guidelines need to be reviewed.

This week's announcement that Pip Orchard will be appealing his 30-month prison sentence for importing 3g of a Class 'A' drug, cocaine, has initiated the kind of public debate his Defence Advocate hoped it would generate.

Advocate Sam Steel - who described the Richards Guidelines for drug sentencing as "notoriously severe” - will be leading the case when it goes to the Court of Appeal next month.

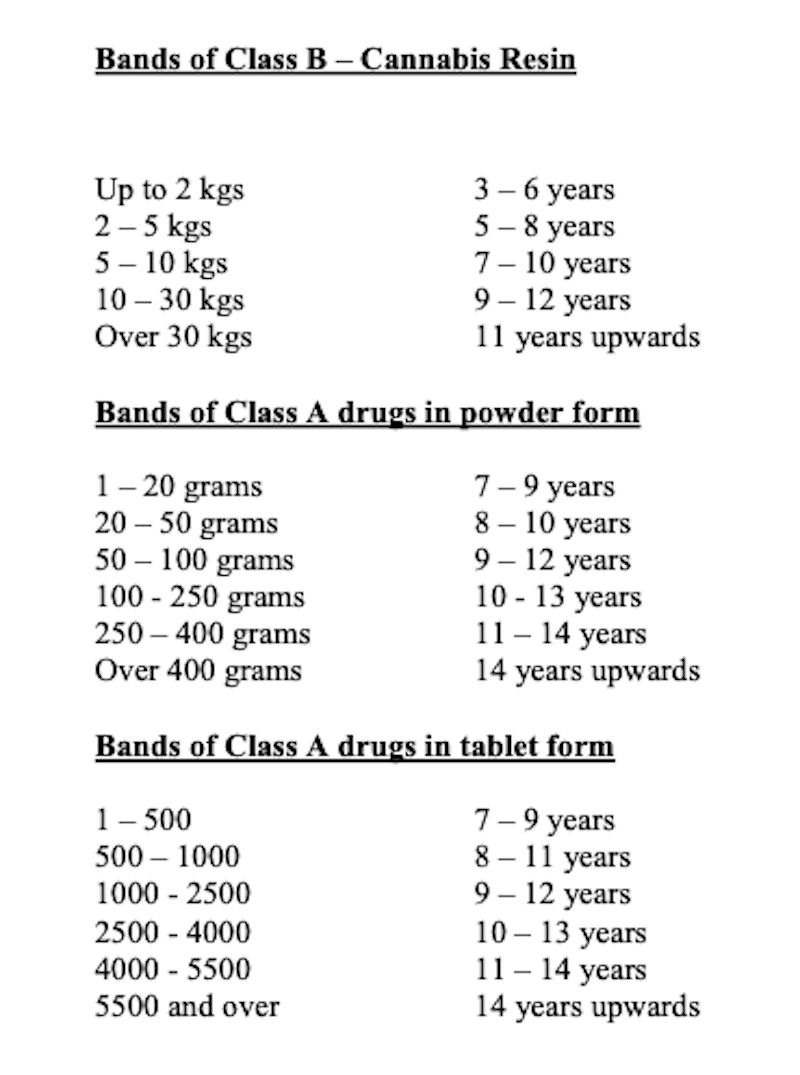

The Richards Guidelines - explained in full HERE - set starting bands for importations and supply. They also instruct that personal use should "not generally result in a lighter sentence" as all drugs, no matter how small the quantity, "add to the stock in the island".

He wants the establishment to review the experience of other jurisdictions, the impact of custodial sentences, and rates of re-offending.

The other element he wants to draw forth is public opinion, both for and against the relaxation of such laws, as part of a society-wide review of the illegal activity and its sentencing regime - both of which can change lives.

Deputy Gavin St. Pier wants the States - as law-makers and policy-makers - to have a serious conversation around drug sentencing. He has argued that treating drug dependency as a health-related issue "will be a huge step forward".

Pictured: The starting points set by The Richards case.

When the guidelines were first enshrined in law, it was a response to the growing problem of drugs misuse across Europe. As Defence Advocate Chris Green observed to Express, they helped to fix what, at that time, was a very real sentencing conundrum.

“The Court of Appeal’s intent, in laying down these guidelines in the highest Court possible, was that every case would fall into these guidelines for the sake of clarity and consistency,” said Advocate Green.

"Before Richards there was a culture of quoting from various different cases and that didn’t tend to help. As an Advocate now, you wouldn’t get very far quoting a case other than Richards.”

For the Head of Bailiwick Law Enforcement, Ruari Hardy, it remains an area of significant concern and one that the Guernsey Border Agency invests substantial resources into.

Mr Hardy says the harm caused by drugs and by the people who trade in them "cannot easily be overstated".

"Aside from the deaths caused by Class A drugs, the addiction, mental health issues and violence follow as a direct result of drug trafficking."

"I am not aware of any positives that come from the misuse of drugs, only negatives. It is an industry driven by organised crime and keeping our community safe from it will remain a key focus."

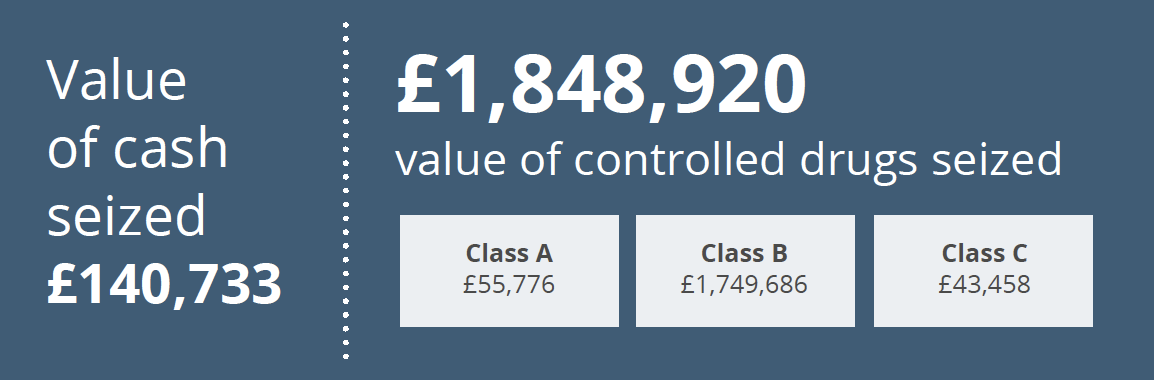

Pictured: A vast majority of the drugs seized in 2020, in terms of value, were Class B substances such as cannabis resin and herbal cannabis.

A study by external consultants Do It Justice and Crest Advisory - completed as part of Home Affairs' 'Justice Review' - makes for interesting reading, as does the independent report commissioned by the previous HSC Committee into alternative methods of drug sentencing.

The Do It Justice study was conducted in 2019. When it came before the States for debate early last year, the previous Home Affairs withheld its support and did not ask the States to support any of its individual recommendations or findings.

During the same timeframe, Dr Harry Sumnall of Liverpool John Moores University was engaged by the States with the brief to review the international evidence base on health-orientated, non-custodial approaches to the possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use.

When asked for a response to the report in June, current HSC President Al Brouard told States members that while it contained some "useful" information, months and potentially years' more work is needed.

Both committees have emphasised the importance of rolling this work into the wider Justice Review, which is prioritised as part of the Government Work plan. Senior politicians on both committees have stressed that justice does not sit squarely within the domain of their own committees, but as a responsibility of the entire States Assembly.

Deputy Brouard recently stated that HSC's main focus is on "identifying the health, wellbeing and safety of people who use drugs".

"It sounds very simple to say we’ll just look at alternatives but we have to have engagement with the community," he said.

"We have those who lobby from time to time from a particular part of our community and we have people in our community with a very different view who haven’t yet lobbied us or come forward."

"We need to take all the community with us, not just those who are in my inbox. When you actually start to unpick it, it is very easy to say ‘no’ and have a very tight society that doesn’t allow drugs in.

"It is very difficult to open it up to just allow a little bit – what do you do with the drug dealer, how do you allow the drugs in, do you look at importation, is it one strike and you’re out?"

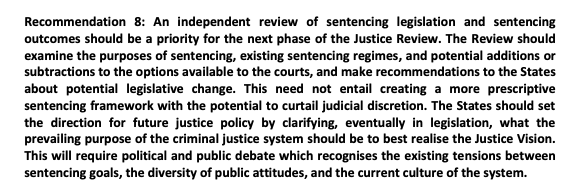

The Do It Justice review also calls for more evidence, engagement and review, saying that all of its own findings should be "tested" further.

The review challenges what Guernsey's justice system is actually trying to achieve and why. There is limited insight to be found in the current legislation.

Pictured: Pip Orchard was sentenced in December 2020 to 30 months in prison for importing 3g of cocaine for his personal use, compared to six months for dangerous driving, in which he led officers on a car chase up Le Val de Terres while drunk. He is appealing against his importation sentence in a test case against The Richards Guidelines next month.

It notes that there is no overarching “justice law” or “sentencing law” in Guernsey. For example, maximum sentences are prescribed, there are guidelines for sentencing some offences - but not others - and the various legal provisions which make up sentencing policy have never been systematically reviewed, apart from the youth justice provisions in the Children Law.

The current legislation - in all areas - is so lacking in direction and objective that Do It Justice decided to go beyond the remit of its own review to challenge the "piecemeal" way in which it was constructed.

"It has not been possible to assess comprehensively the extent to which sentencing practice accords with the objectives of the current justice strategy, including with the justice vision," said its author, Gemma Buckland.

"This is due to both a lack of data and a lack of clarity about how the overall sentencing regime— which forms a crucial component of justice policy—maps across to the strategic outcomes intended. In practice, sentencers will seek to balance in their decision-making various considerations which may relate indirectly to the strategy.

"The absence of clearly stated principles or objectives specifically for sentencing policy makes it challenging to determine what contribution this element of the system should be making to the impact of the overall policy.

"We therefore consider that any major transformation of justice policy must include a review of sentencing policy, which was not within the scope of this phase of the review."

Pictured: Recommendation 8 of the Do It Justice report was 'noted' by the States, however no action has been taken on this or any of its other conclusions or recommendations.

One of the consequences of not having an overarching policy is that the sentencing of some offences do not sit right compared to others.

Ms Buckland said: "There was a strong perception among some representatives of justice agencies and service users who engaged with us that the current response within the criminal justice system is overly punitive for some offences and not sufficiently strong for others.

"This is particularly the case for the treatment of sexual offending, especially against children, compared with offences related to drugs, for example, with sentences for non-violent offences, such as the possession of drugs, being perceived as being treated more severely, or on a par with, sexual and violent crimes when the latter were considered to warrant a more punitive response due to the higher levels of harm."

"Another issue raised with us frequently throughout our consultation was the treatment of alcohol-related disorder compared with disorder connected to personal drug use. This view was borne out more broadly in responses to the public survey in which alcohol was identified as the biggest problem facing society in the Bailiwick.

"It is important not to shy away from these questions within a democracy in which there are differing, strongly held views and possible generational differences in perspective.

"Respondents to our survey identified alcohol abuse as the biggest problem facing Guernsey today, and drug dependence as the fourth biggest problem (behind domestic abuse, and poverty and inequality)."

Pictured: Every two out of five crimes is committed under the influence of alcohol.

The price Guernsey pays for this is reduced confidence in the judicial system among the community it is there to protect and to serve. 52% of respondents to a Do It Justice survey were “not very” or “not at all” confident that the Bailiwick’s criminal justice system as a whole is fair to all, compared with 20% who were “very confident” or “fairly confident”.

Further public engagement and review is necessary, says Ms Buckland, in order to better understand these concerns and offer a greater level of transparency into the judicial process.

"It is wholly legitimate for historical perspectives about the nature of responses to criminal justice matters embedded in existing legislation to be reviewed and refreshed, to ensure that justice policy is fit for the 21st century, takes into account contemporary criminological evidence, and is financially sustainable," she said.

"The lack of data about the administration of criminal justice and how the existing sentencing regime operates in relation to different types of offence means that the contribution of current sentencing practice to justice policy and its desired outcomes is not sufficiently transparent. This may contribute to perceptions of unfairness amongst some people and warrants clarification."

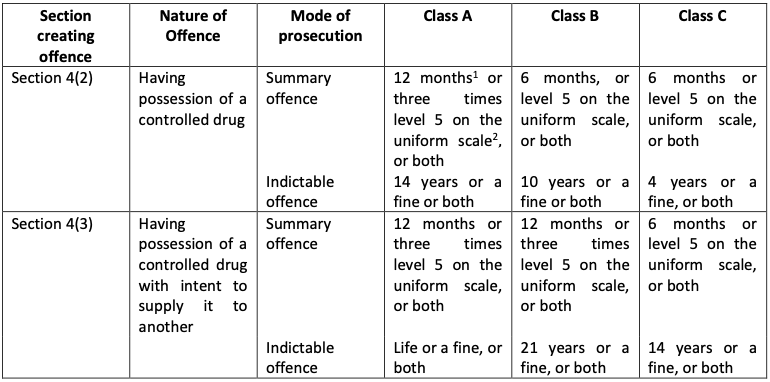

Pictured: Sentencing powers for drug possession and possession with intent to supply offences under the Misuse of Drugs Law 1974. Table shows the maximum sentences - the indictable offence - that can be handed out.

Do It Justice asks whether there is scope for greater diversion from the system through a wider range of sentencing options.

Work to this effect was approved by the previous States following a successful amendment led by former Deputy and HSC member Emilie McSwiggan, who was unhappy with the speed at which Home was proceeding with its work on the Justice Review.

The subsequent research carried out by Professor Harry Sumnall of Liverpool John Moores University was published last July.

"The potential health and social harms and costs to individuals and communities associated with substance use and criminal markets are significant and well-characterised," he wrote. "However, unintended harms may also indirectly arise as a consequence of drug policy, and the legal responses to drugs.

"The international literature suggests that a criminal record associated with a drug-related offence can have long-lasting consequences for an individual’s (mental) health, life chances, and wellbeing. A conviction may impose restrictions on employment, international travel, and residency."

Pictured: In 2019, Luxembourg announced preparation of draft legislation leading to the legal regulation of cannabis. Proposed restrictions include a ban on sales to non-residents and home-growing, and a personal possession threshold of 5g.

There is emerging evidence, he wrote, from a number of countries that alternative approaches can reduce criminal justice costs and increase the number of referrals to support services for those who need them.

When the Court of Appeal decided back in 2002 to impose the Richards sentencing guidelines, it was done on the basis that “misuse of drugs is one of the scourges of European society at the present time".

It stated: “This Court is not attempting to establish for the Royal Court some sort of inflexible code, which covers all of the issues involved in sentencing for such offences, some of which must as yet be unknown and incapable of anticipation."

Referring to some of those international models, Professor Sumnall outlined how - at the time of writing - 12 EU countries had outlawed custodial sentences for possession of small quantities of cannabis (Bulgaria; Croatia; Czech Republic; Ireland; Italy; Latvia; Lithuania; Luxembourg; Netherlands; Portugal; Slovenia; Spain).

There are three main alternatives to the current sentencing regime, according to Professor Sumnall. These are:

Depenalisation - the reduction in severity of custodial sentences for drug possession. Punitive sanctions may also be replaced by warnings or cautions, opportunities for diversion into drug screening, education and/or treatment programmes.

Decriminalisation - the formal process of removing criminal penalties for drug possession offences. This can be provided in law, or in sentencing guidelines. Under decriminalisation, possessing less than a legally defined amount of a controlled drug no longer leads to an individual being punished through a criminal record or custodial sentence. For repeat offenders, there may be diversion into targeted support that aims to address use of drugs and/or offending behaviour.

Diversionary activities - these can take place without depenalisation or decriminalisation of drug possession. This means they could be used without any change in the legal framework, or as an interim measure ahead of further changes.

One such approach has been delivered by Thames Valley Police (UK) since 2018. Instead of being arrested for breaking the laws, people found in possession of any substance are eligible for community-based support and drug service referrals.

Pictured: Around a third of the prison population at any one time is made up of people convicted for drug possession, supply or importation.

Checkpoint is a voluntary adult offender programme operating in Durham Constabulary that targets low-level offenders entering the criminal justice system by providing an alternative to criminal prosecution, which is deferred while attempts are made to resolve underlying issues.

This approach differs from the Thames Valley Police model as participants agree to adhere to a "behavioural contract" with a number of conditions, and are supported by a case worker who offers "substantial and meaningful contact".

If participants re-offend or do not engage with their case worker, the contract is considered to be breached, and all suspended prosecution proceedings are re-activated.

If the conditions of the contract are satisfied, then the matter is resolved by the way of a 'community resolution' - a non-statutory method that is not disclosed on background checks.

Portugal also offers a well-known diversionary approach. A person caught using or possessing less than the threshold amount of a drug for personal use, where there is no suspicion of involvement in supply, is referred by police for an evaluation by a 'Commission for Dissuasion of Drug Addiction', which carries out an individual assessment.

Punitive sanctions can still be used, but the main objective is to explore the need for further support, so clients can be referred to local services, including drug treatment, (mental) health and social care, employment support, education, and child protection.

Pictured: Harry Sumnall is a Professor in Substance Abuse at Liverpool John Moores University.

Professor Sumnall concluded his report by saying there is a rich evidence base of "contemporary" approaches to sentencing of drug possession, all of which can be "learned" from and potentially applied to the Bailiwick, subject to full review and consideration.

"Importantly, all the approaches presented in this report are compatible with international drug control conventions, and contemporary international drug policy norms in comparator countries, that have been moving towards less punitive approaches to possession offences over the last few decades," said Professor Sumnall.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.