The first joint review into nuclear risks to the Channel Islands has concluded there continues to be an extremely low risk of a radiation incident from nuclear activities in northern France or the tens of thousands of barrels filled with radioactive waste dumped in Hurd’s Deep.

It’s a refresh of work carried out years ago, with Guernsey last reviewing risks in 1997, while Jersey last reported on it in 2007, to update plans and procedures should disaster strike.

The report, written by the UK Health Security Agency, reassures islanders that nuclear disaster is unlikely - but sets out steps that could be taken in the unlikely event of a nuclear disaster.

Officials in both islands have voted unanimously to not stockpile iodine tablets locally, which can prove effective against thyroid cancer if exposed to the common element during radiation emergencies.

Sheltering in place is instead viewed as the most effective response in the event of a nuclear incident where a plume of radioactive materials could pass over the island from nearby sites.

But emergency and public health teams say it’s “very unlikely” such an event would unfold, and even if it did modelling of the past five years of weather including 850 computer simulations show that prevailing winds are likely to push plumes away from the islands.

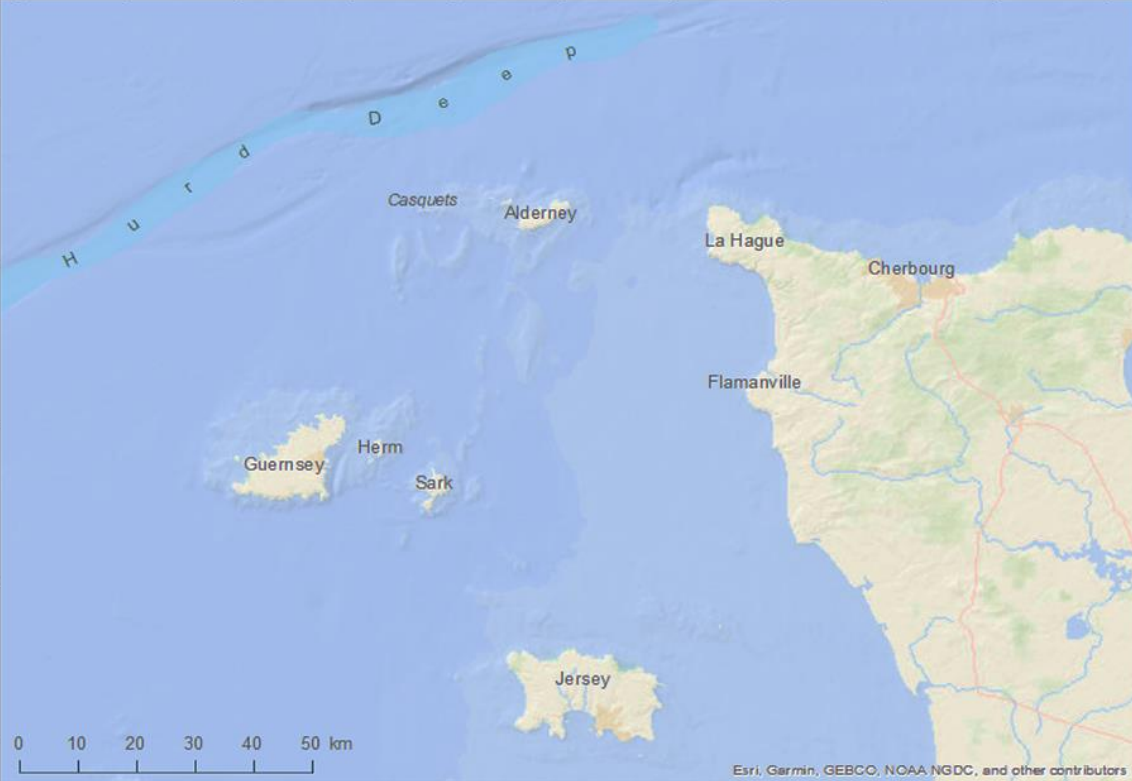

The teams also praised French safety officials and protocols following site visits to the Flamanvile nuclear power station, the Orana La Hague nuclear fuel reprocessing site, and the Cherbourg naval dockyard which commissions and decommissions nuclear submarines – all located nearby on the Cotentin Peninsula.

Marine risks from the transport of nuclear materials were found to be low due to stringent controls on storage methods, while annual test samples linked to the radioactive waste dumped in barrels in Hurd’s Deep – the deepest part of the Channel just miles from the islands – continue to show negligible results.

Pictured: Flamanville, La Hague, Cherbourg, and Hurd's Deep all host nuclear materials.

Researchers focused on the largest nuclear accidents, which are very rare, in relation to the three French sites. A disaster would see a radioactive plume leave the original site.

Considering factors like the wind, they found that a radioactive plume could take just one hour to arrive in the Channel Islands - but that it could also take four to 12 hours or even be blown in the opposite direction.

Once the plume is on its way, islanders are likely to be asked to shelter in place - going inside buildings, closing doors and windows, and tuning off fans and air conditioning. They could be asked to stay there for a several days.

This, however, means that people could find themselves separated from their families, or unable to access medical care or assistance.

The report also finds that evacuating people from the islands would be unrealistic, and that people would need "advice" on what to eat or drink - as any food that is unsealed or not yet harvested could be contaminated.

Nevertheless, they said at least half of the plumes modelled either did not pass over the Channel Islands at all or had very low radiation levels.

Pictured: France has one of the largest nuclear power systems in the world.

The UKHSA has recommended that marine samples continue to be collected alongside plans to deal with radioactive releases into local waters.

It also called for continued dialogue with French authorities and having a detailed communications plan for the public should the worst come to pass, but also in the event “no action is required” to provide reassurance.

Dr Nicola Brink, Guernsey’s Director of Public Health, said modelling has improved since 1997 and this report focuses on the worst case scenarios.

“We wanted to find out what we would be facing in the worst situation - so in the unlikely event of an incident happening and the unlikely event of the prevailing wind blowing towards the Channel Islands. Despite this, it was a very reassuring report,” she said.

“What was also important was meeting the emergency planners [in France] and making sure that we have some direct communication with them because that direct communication will save us time in the unlikely event of something happening.

“So building those relationships, but also being able to see it ourselves so that we can come back and communicate to slanders what we've seen we felt was very important.”

Professor Peter Bradley, Director of Public Health for the Government of Jersey, sought to reassure over the decision not to stock iodine, saying it was impractical and ineffective against many forms of radiation.

“Stable iodine tablets would only be necessary in one specific scenario, coupled with the significant practical challenges of ensuring timely and secure distribution of the tablets to the community,” he said.

It was noted by Kelly Jones of the UKHSA and author of report that levels of radiation detected in marine samples are much lower than other sources such as radon gas and air travel.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.