With warmer weather and with changes aplenty in the night sky this month, Elaine Mahy from La Societe Guernesiaise's Astronomy Section makes the case for spending more time observing the stars and planets.

"March is a month with lots of change, and several interesting events to observe.

Constellations

The bright winter constellations of Orion, Taurus, Gemini and Canis Major are prominent in early evening, with Leo the lion taking centre stage later, passing high in the south around midnight. Below Leo is a sparse region of sky containing the long and winding constellation of Hydra the snake, however in the SE bright Spica rises in Virgo and to the east, bright orange Arcturus in Bootes is also rising; these become prominent to the south by midnight towards the end of the month.

Looking northwards during the evening bright Vega in Lyra rises to the NE, followed by Deneb in Cygnus. Polaris, the North Star, sits at 49 degrees above the N horizon, framed in one direction by the ”W” of Cassiopeia moving from NW to low to the north, and in the other direction by Ursa Major (with asterism the Plough) which rises to almost overhead and upside down around midnight. To the WNW bright Capella in Auriga descends during the evening, almost touching the northern horizon by dawn.

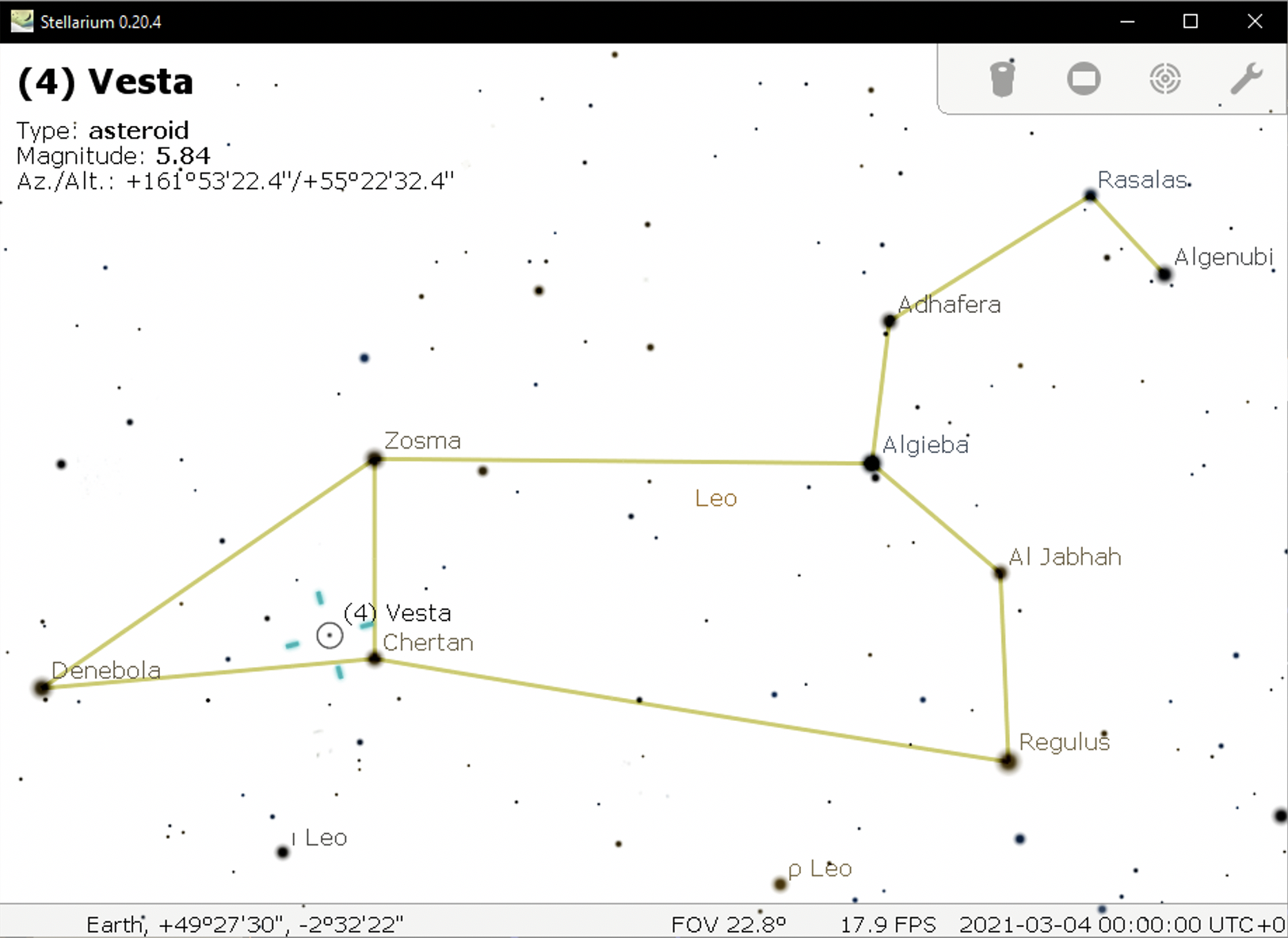

Pictured: On Friday 26 February, Mars was directly below the Pleiades. The planet will pass between the Pleiades and Hyades star clusters on 8 March.

Planets

Mars remain easily viewable through March in the evening, from SW to W while moving eastwards through Taurus. Uranus moves towards the sunset in the west but can still be seen in Aries in March as a faint blue dot in binoculars – you will need a star chart.

Saturn and Jupiter may be spotted before dawn very low in the SE, with Mercury between the pair at the beginning of the month, passing Jupiter on 5 March; unfortunately all in a poor position. Venus is behind the Sun and not visible in March.

Milky Way

The brightest part of the Milky Way, the central part or core, in Sagittarius, is becoming visible around 4-5am, before sunrise. The second and third weeks of March have no moon so if you’re up very early, find a very dark, clear view to the SE horizon and see if you can find Sagittarius rising in the SE and as your eyes get used to the dark, try to spot the diffuse whitish glow of our galaxy’s core. Later during April to August the Milky Way rises higher and at earlier times.

Photographs can be taken of the Milky Way using a long exposure, or a sequence of shorter exposures stacked together.

4 March - Asteroid Vesta at opposition

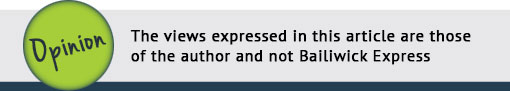

First but maybe a little tricky to observe, asteroid 4, Vesta, can currently be found in the prominent constellation of Leo, which is visible all night, and is highest to the south around midnight. Vesta reaches opposition on 4 March reaching magnitude 5.84 and if you have binoculars or a suitable camera and tripod it could be a fun exercise to track it night to night as it takes a looping tour through the constellation of Leo over the next three months – though it is brightest during March.

Use a planetarium app such as Stellarium (diagram shown) to find and track Vesta each night. Vesta may just be visible to the naked eye from a dark location once your eyes are dark adapted, or it can easily be found with binoculars.

Mars passes between Pleiades and Hyades star clusters on 8 March

In early March you can view the movement of planet Mars day by day as it approaches and passes up between the Hyades and Pleiades star clusters in the constellation Taurus. Look for this around 8pm to the WSW, to the right of the Orion constellation. Bright red Mars at magnitude 1 will look similar to orange star Aldebaran. The area is also great in binoculars, or if you would like to try photographing the sky this might be a good place to start. See the Stellarium chart below, showing the path of Mars and its position on the 8th.

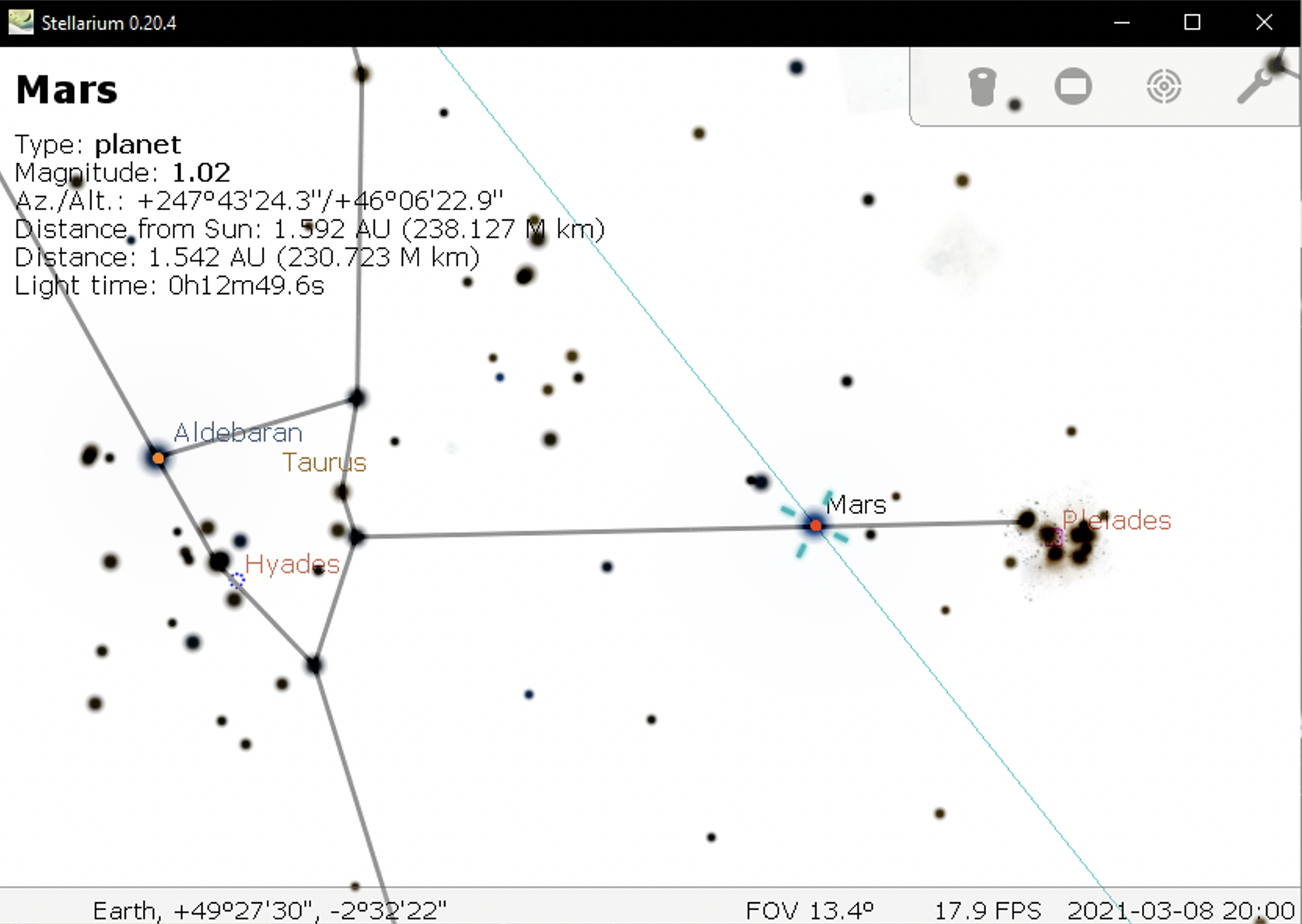

15-16 March - Earthshine on the Moon at dusk

Ever seen the dark side of the moon? Earthshine, or the Ashen Glow, can sometimes be seen filling in the rest of the circle of a thin crescent moon. This occurs soon before or after New Moon, visible near dawn or soon after sunset.

Why does this occur? Well, at the thin crescent phase, if we were standing on the Moon facing Earth, the phase of the Earth would be gibbous or almost full, reflecting a lot of sunlight back at the Moon. Earth is bigger and more reflective so Earthshine is about 100 times brighter on the moon than a full moon seems on Earth.

How can we see earthshine? The 1-3 day old waxing crescent moon occurs between 14-16 March, and in late winter months and through spring, the dusk crescent moon is relatively high so can be observed and photographed to the West for an hour or two after sunset. Perhaps best on 15 March with the 2 day old moon, wait until the sun has fully set and the sky starts to darken, and scan the western sky.

Once the bright crescent is spotted, earthshine may become quite prominent in the right conditions, showing details on the dark portion of the crescent Moon. In effect this is light that has been bounced from Sun-Earth-Moon-Earth, having travelled a different path from the light on the bright part which has travelled Sun-Moon-Earth.

The effect can also be seen in a crescent moon before dawn late summer / autumn.

If you have a camera with manual adjustments, try photographing the moon at different exposures. Use a tripod if possible to avoid shake.

20 March - Spring (Vernal) Equinox

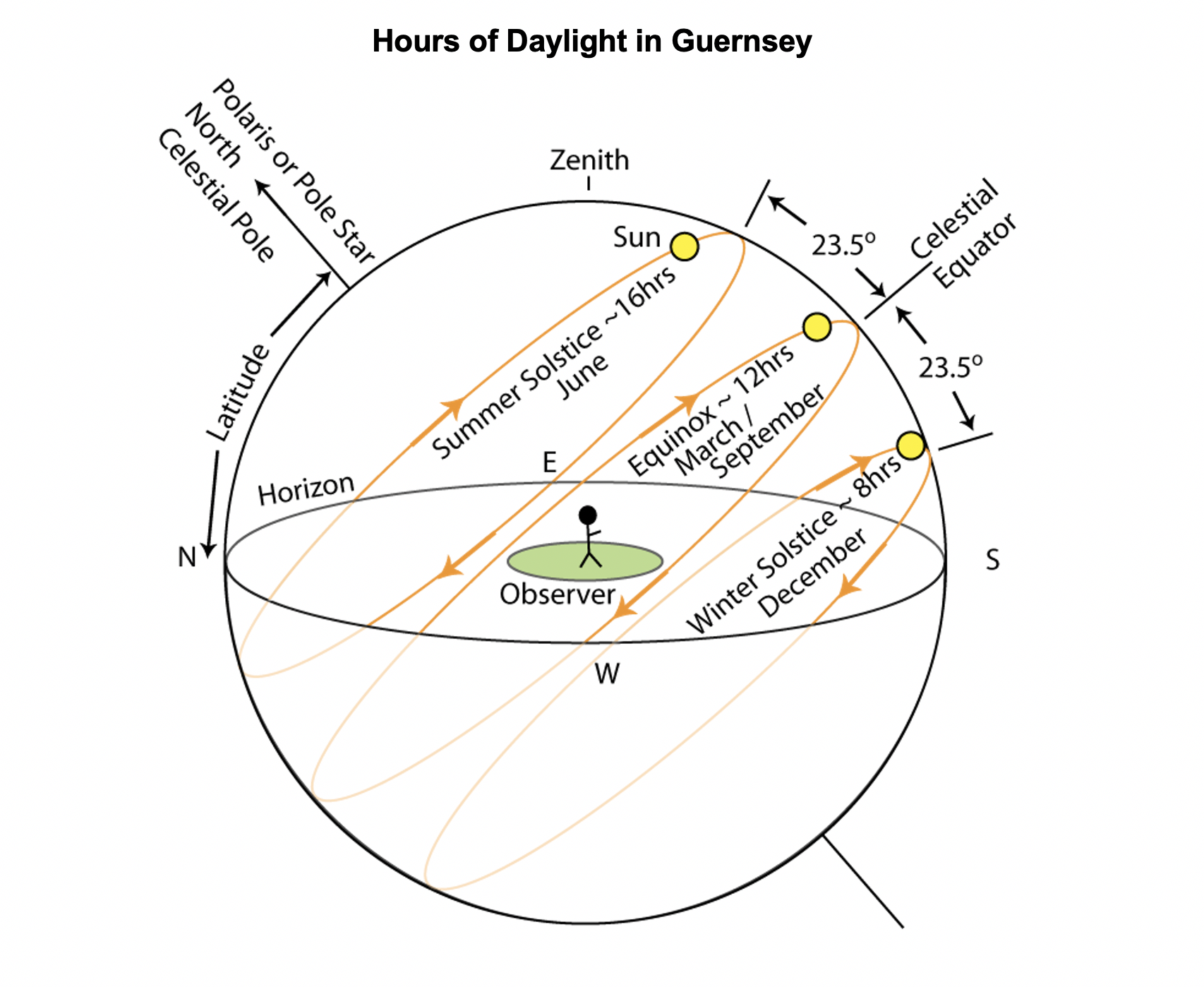

March is the month of the Spring Equinox in the Northern Hemisphere. On 20 March the sun will rise almost exactly in the East and set almost exactly in the West. On the equinox there are about 12 hours of day and 12 hours of night as Earth’s axis lies perpendicular to the Sun’s light.

The Sun’s position on its apparent path through the stars, the ecliptic, crosses northwards through the celestial equator on this date. Through spring and summer until the autumn equinox, the sun will rise north of east and set north of west, and rise higher through the south, with its longest and highest path at the summer solstice on 21 June when the daylight lasts around 16 hours for us in Guernsey. In winter, the sun appears below the celestial equator and we have shorter days, about 8 hours long in Guernsey at the Winter Solstice on 21 December.

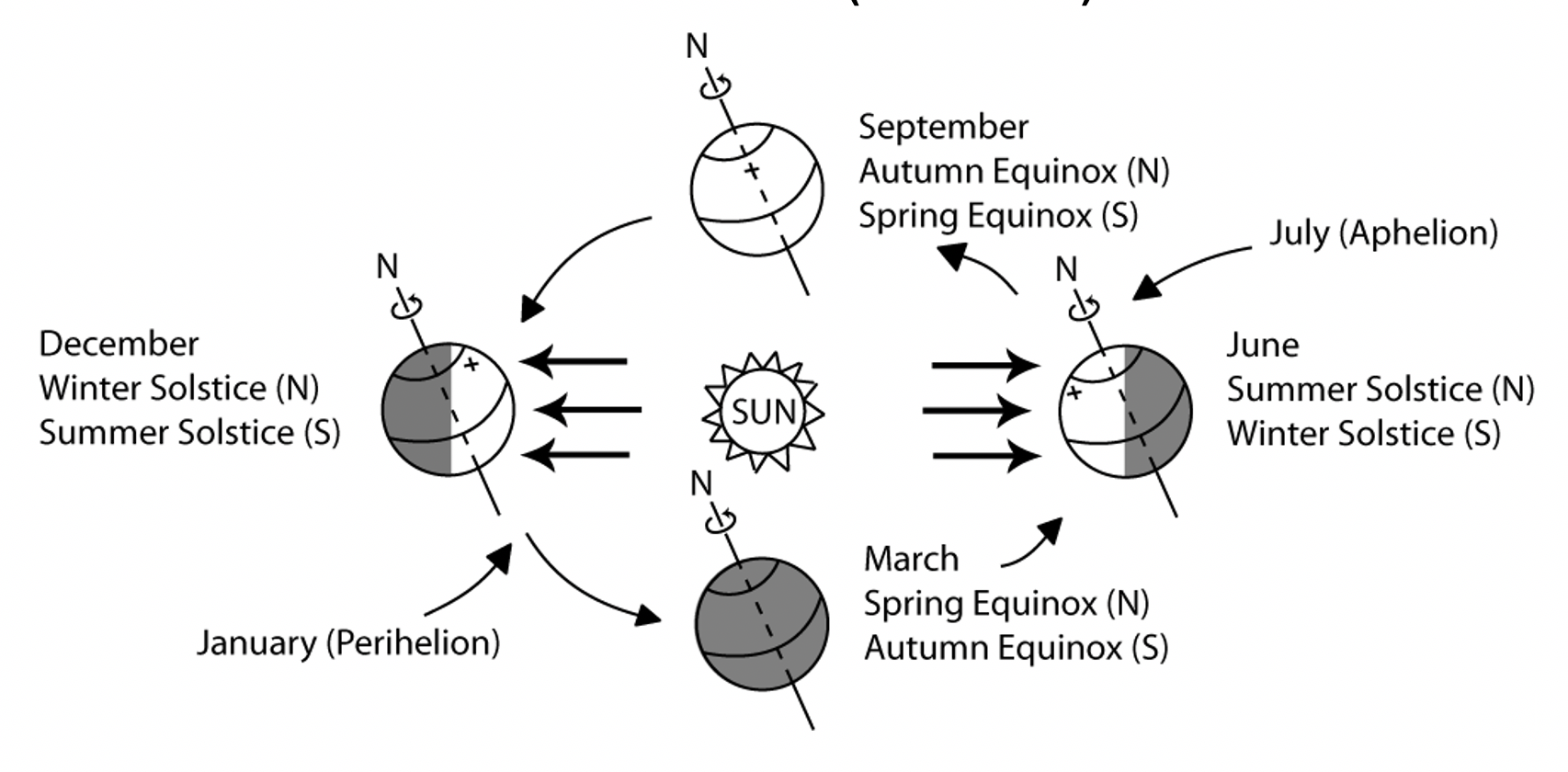

Why do daylight hours change so much? Our planet’s axial tilt, currently 23.5 degrees in relation to our orbit around the sun, causes parts of the globe to experience different seasons at different times of year. In winter the North Pole is angled more away from the sun, so the sun appears low and its warmth is reduced as sunlight arrives at a shallow angle via a longer path through our atmosphere. In summer when the North Pole is angled more towards the Sun, the Sun appears high and more of its heat reaches us from a steep angle through our atmosphere.

In an opposite fashion, the Southern Hemisphere experiences midsummer in December and midwinter in June.

At equinox, halfway between winter and summer, the Earth’s axial tilt lies evenly across the sunlight, with neither pole favoured while the Sun is crossing the Celestial Equator, and the whole planet receives approximately 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of night.

Earth’s Seasons (not to scale)

Is the day really exactly 12 hours long at the equinox? Well, not quite. Daylight is calculated when only an edge of the sun is visible – so we gain a few extra minutes from a sun-width. And refraction of sunlight at sunrise and sunset through our atmosphere actually bends the sunlight further around so we see sunrise earlier – and sunset later – than they would seem if we had no atmosphere. So this year at the Spring Equinox, in Guernsey, the day will be 12 hours 11 minutes long.

The weeks around Spring Equinox are also a time of change. Each day is about 4 minutes longer than the day before, with the sun rising higher in the sky; and the dark evenings get a lot later with the changes to the clocks also factored in for British Summer Time.

At the start of March in Guernsey, sunrise is 06:52 and sunset is 17:53 GMT. At the end of March, sunrise is 06:49 and sunset is 19:40 BST – almost two hours later.

The clocks change from Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) to British Summer Time (BST) on 28 March when we set our clocks to an hour later, “losing” an hour.

To learn more about astronomy or astrophotography, visit www.astronomy.org.gg; find contact information, activity ideas and details of our events and regular members’ activities which we will resume once we are able. We also have a Facebook page, La Société Guernesiaise Astronomy Section.

The Astronomical Observatory of La Société Guernesiaise remains closed for the time being during lockdown stages, though we hope to welcome members and visitors back soon.

In the meantime as the weather warms up do take some time to look around the sky on a clear night; try to see some of the events, and take note how fast the season changes.

Pictured top: The Pleiades open star cluster, also known as M45 or the Seven Sisters, in the constellation of Taurus. All photos and diagrams supplied by Elaine Mahy.