Ahead of this week’s special meeting of the States, to discuss the Annual Report of the Government Work Plan and the States Accounts for 2022, Richard Hemans, the Institute of Director’s (IoD) Guernsey lead for local economic matters shared his thoughts on the 2022 accounts:

The Guernsey branch of the IoD welcomes the progress the States is making on the long journey to a set of robust, complete, recognised public sector financial statements.

The 2022 financial statements include the social security funds and recognise the material fixed assets the States owns to offer a more comprehensive view of the financial performance and position of the island. However, it is neither clear what remains to be included to complete the full transition by 2024 (except the consolidation of the publicly owned trading entities), nor what changes will be encompassed in 2023 and 2024.

There are still a number of presentational and explanatory adjustments that could be made to improve understanding. For example, 2022 consolidates general revenue and social security but offers no like for like comparatives, which would be easy to provide by simply adding social security to the 2021 numbers. Similarly, the 2021 figures are restated but it is not made clear what exactly has been restated.

The complexity of the States accounts is demonstrated by the fact that whilst the overall net deficit is a staggering £135m, the States actually generated £37m of cash in 2023. This is truly mind-boggling and underlines the difficulty of evaluating the States financial position. The cash was generated mainly from the sale of investments, which is clearly not sustainable in the long term.

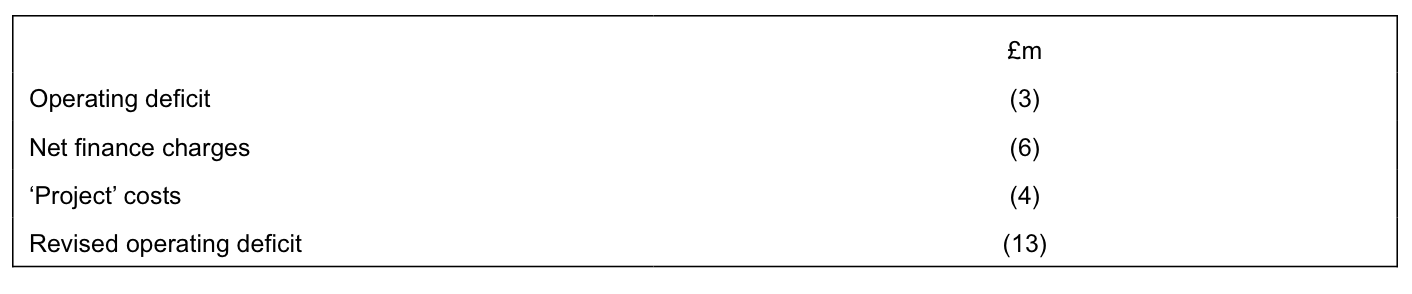

The net deficit of £135m needs to be distilled properly to make it relevant for understanding and decision-making as we strive to make our public finances sustainable in the long term. Non-cash, volatile items such as investment returns and depreciation totalling £123m need to be added back. Net finance charges and income of £4m need to be unpicked to identify the cash items to deduct, which are actually £6m (there are some very large, unexplained items in finance charges such as a bad debt credit of £15m and an investment impairment of £12m that need more scrutiny than can be provided here). Finally, there is the mysterious ‘contribution towards project costs’ of £4m that was also deducted in the prior year and therefore we shall assume it is cash-based and recurring.

The States Accounts therefore indicate that the island ran a net deficit of £13m in 2022, which is based on current operating expenditure and excludes capital expenditure. This includes the £16m social security deficit so we can identify a £3m surplus on general revenue and £16m deficit on social security.

Including the States approved capital expenditure target of 3% of GDP that deficit increases to nearly £120m. It is against this fiscal backdrop that the Government Work Plan, which sets out new services and projects, must be considered. The States need to produce an operating surplus to finance the island’s capital investment without resorting to additional borrowing or drawing down further on the island’s dwindling reserves.

Given States expenditure is in excess of £800m we could argue that a reduction of at least £20m is possible, but this would only deliver a small surplus and leave the States still needing to find nearly £100m to finance the capital investment. But this is based on current spending and a relatively buoyant economy, which is under severe pressure from the ageing population, rampant inflation and the unaffordable spending plans of the States.

The States Accounts underline this problem neatly. Overall tax receipts have fallen in real terms although this conceals a significant decrease in employee earnings, which represents the majority of income tax, and a significant increase in company profits, which are taxed more narrowly. Whilst income is falling in real terms, costs in the form of pay, the largest element of States expenditure, were flat in real terms, thereby contributing to the widening deficit.

Guernsey is currently unable to finance existing services and capital expenditure without borrowing more, depleting reserves, selling assets, reducing costs or raising tax. Put simply the island is living beyond its means.

The current deficit will likely deteriorate further because of high inflation, the economic cycle, the backlog of capital expenditure and the ageing population before even accounting for new services. The public finances are unsustainable.

In the short term, we need to agree how we are going to finance current services and capital expenditure, which will inevitably involve increasing taxation significantly if we don’t want to exhaust reserves, sell the family silver or borrow more. Essential new services will need to be factored into this plan, but may need to be deferred or substituted for existing services.

Guernsey needs to be careful, however, that we don’t strangle the economy by increasing taxation too far and therefore we need to prioritise services and capital expenditure whilst recognising that we cannot do everything given our scale. The States fiscal target allows it to collect taxation just shy of £1bn, which gives capacity but we must not undermine our competitiveness and attractiveness in doing so.

In the medium term we need a root and branch review of government – its scope, scale, cost, structure and delivery, and how to finance it. Ideally this would be done first, but the real fiscal deficit needs to be addressed now. By increasing taxation, the States would not only close the deficit but give itself the flexibility to resolve the fundamental mismatch between the scope and scale of government and our ability to finance it. This will take real political leadership and commitment.