When six drug smugglers attempted to import a mixture of Class A and B substances into Guernsey in 2001, little did they know that their case would become a reference point for years to come.

The way that Guernsey’s Courts deal with drug importation, supply and intent to supply cases is based on the precedent set by a Court of Appeal judgment 19 years ago.

The case is known in legal circles as Richards 2002; the year that six of the defendants chose to appeal their original sentences. The scale of the case saw the Court of Appeal beef up its membership from three judges to five, including the Bailiffs of both Guernsey and Jersey, Sir de Vic Carey and Sir Philip Bailhache.

They viewed the appeal as the right moment to formulate guidelines in the highest court possible, given that many of the earlier cases cited by lawyers were regarded as being “deficient, in that they do not address issues of quantity or attempt to establish any level of bands depending on the size of the consignment.”

“Misuse of drugs is one of the scourges of European society at the present time,” the judges said in their formal judgment back in 2002.

“The Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey have not escaped the attention of those who wish to make money out of corrupting the inhabitants of these islands into becoming addicted to drugs for which they will pay large sums of money.”

Their judgment delivered a clear marker for defence advocates, stating that “from now on, it should be unnecessary for counsel to refer the court to earlier cases in the Guernsey courts.”

In September 2001, Mark Richards (who was based in the UK) was caught importing 205.43g worth of Ecstasy powder into the island with a purity of 71%.

The package was sent from South Wales and was intercepted at Guernsey postal headquarters. On interception, a dummy package was substituted for the powder, with the authorities using that to track down the others involved.

At the time it was, by some margin, the largest single consignment of Ecstasy imported in any form into the Bailiwick and had a street value of £45,000 to £54,000. Richards was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison for his part in the drugs run.

Hautermann was perhaps the most notable of Richards’ co-defendants. The German national, who claimed he was coming to Guernsey on a fishing trip, was arrested after his BMW - which had arrived on the ferry from Jersey and St. Malo – was found to contain 14.8kg of cannabis resin and 100g of cocaine.

Those two and three others - Michael Skelly, Ian Garven and Gareth Canning – had their appeals rejected, while Martyn Noyon’s sentence was reduced from four-and-a-half years to three-and-a-half years on appeal.

Richards' two Guernsey-based accomplices did not appeal their sentences.

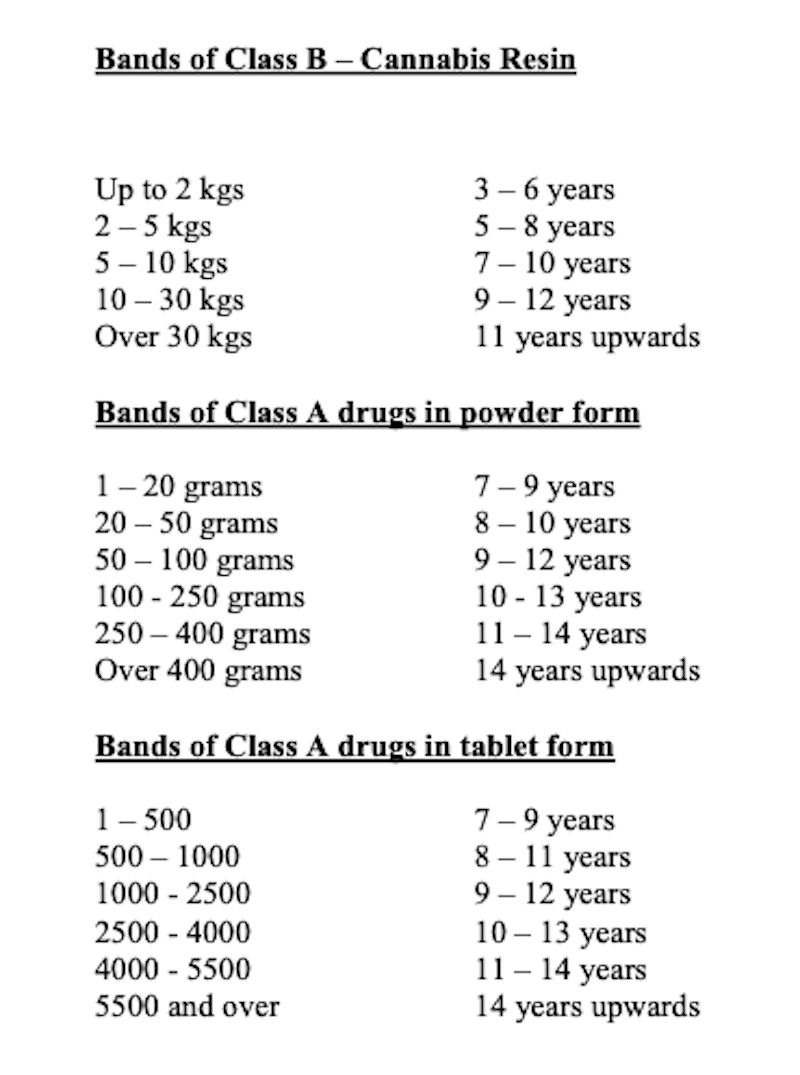

The maximum sentences were already laid down by the States – life imprisonment for the importation of Class A, 21 years for the importation of Class B drugs, and life imprisonment for possession with intent to supply either class of drugs.

The trickier exercise was setting out sentencing bands. Each needed different starting points, from which mitigation and other discounts (for example, for an early 'guilty' plea or previous good character) could be applied.

The following sentencing bands were chosen:

A significant passage of the Richards judgment instructs that personal use should "not generally result in a lighter sentence" as all drugs, no matter how small the quantity, "add to the stock in the island".

"There is a clear division between importations of very small quantities for personal use which are punished in the same way as offences of simple possession, and importations of more than relatively small amounts which still fall within the lower of the bands we have set out," said Sir de Vic.

"In the case of such importations, the fact that a claim is made that a drug was for personal use will not generally result in a lighter sentence being imposed than where no such claim is possible, because any importation adds to the stock of drugs available in the island.

"Although these cases must be looked at with care, it cannot generally be right that an addict importer of the drug to which he is addicted can be heard to claim some credit for the likelihood that he will be consuming all or part of it."

The Richards case became a precedent, setting the bar for all future sentencing. This instruction that was set out by Sir de Vic when he stated: "So that there is no misunderstanding of this Court’s position, guidelines issued by the Royal Court, however clear and well observed in later cases, cannot bind that Court with the same authority as those adopted and promulgated by this Court.

Pictured: The Richards appeal was seen as an opportunity to set down sentencing guidelines in the highest form of Court.

He continued: “We consider that, where appropriate, these guidelines should be taken as replacing all previous guidance and that proper regard should henceforth be paid to them by the Royal Court in imposing sentence.

“The starting point has to be determined primarily by considering two factors, namely the quantity of the drugs and the involvement or role of the defendant in the commission of the offence. In that way the court assesses the extent of the criminal conduct."

It was reiterated then, as it has been in many Royal Court hearings since, that these guidelines are not a “straitjacket”.

“This Court is not attempting to establish for the Royal Court some sort of inflexible code, which covers all of the issues involved in sentencing for such offences, some of which must as yet be unknown and incapable of anticipation,” said Sir de Vic.

“These are general guidelines only. Sentencing is always a matter for the court’s discretion. It is an art and not a science.”

There are grey areas not covered by these guidelines, while there are - increasingly - occasions where Guernsey's drugs laws clash with other jurisdictions.

“In other places around the world he has bought these substances over the counter,” said his Defence Advocate, Sam Steel.

While he avoided prison, he lost out on work in the Gulf of Mexico and Indonesia, two of many jurisdictions that take drug convictions into account when allowing visas.

Other cases have seen the Court exercise its discretion to give suspended sentences to some and impose immediate imprisonment to others.

A young couple benefitted from that flexibility last year when they were both given lengthy suspended sentences and ordered to complete 50 hours of community service after they were charged with dealing 180g of cannabis, before being caught in possession of the drug while on bail.

In other instances, immediate imprisonment has been imposed. Recently, a pregnant mother was sentenced to two years, four months in prison for the supply and importation of an estimated 240 to 280g of cannabis, aggravated by offences committed while on bail and a refusal to disclose her pin code during one of the investigations.

In another recent Royal Court appearance, a 16-year-old who had grown up within a household that promoted cannabis use managed to avoid youth detention for supplying an estimated 34g of cannabis. He was, however, hit with 240 hours of community service, the maximum that can be imposed.

Pictured: Only prison sentences up to two years can be suspended under the current laws.

It shows that there are a wide range of variables - mitigations, early pleas, criminal record and aggravating factors - that help to determine the final judgment, beyond the Richards Guidelines.

However, these remain significant as they set the starting point for sentences, before any mitigations are applied.

“The Court of Appeal’s intent, in laying down these guidelines in the highest Court possible, was that every case would fall into these guidelines for the sake of clarity and consistency,” Advocate Chris Green told Express.

"Before Richards there was a culture of quoting from various different cases and that didn’t tend to help. As an Advocate now, you wouldn’t get very far quoting a case other than Richards.”

“These guidelines are not entirely definitive, but generally speaking the spirit of Richards is always applied."

It has been announced today that Pip Orchard - who was sentenced in December 2020 to 30 months in prison for importing 3g of cocaine - is appealing his sentence in September before the Court of Appeal.

He is being represented by Advocate Sam Steel, who will challenge the Richards Guidelines.

“Our Judges and Jurats have an unenviable task because our sentencing guidelines for drug importations are notoriously severe,” said Advocate Steel.

Pictured: Pip was sentenced in Guernsey's Royal Court and will have that judgment reviewed by the Court of Appeal.

He continued: “Personal use will not generally result in a lighter sentence. I understand why Pip’s many supporters want the guidelines reviewed.

"Such a review could take evidence from a range of NGO’s, the experience of other jurisdictions, current data regarding seizures, arrests and the impact of custodial sentences on the offender and rates of reoffending, and public opinion too.”

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.