A compression bandage that acts as a pressure sensor by changing colour as it stretches has been designed by scientists.

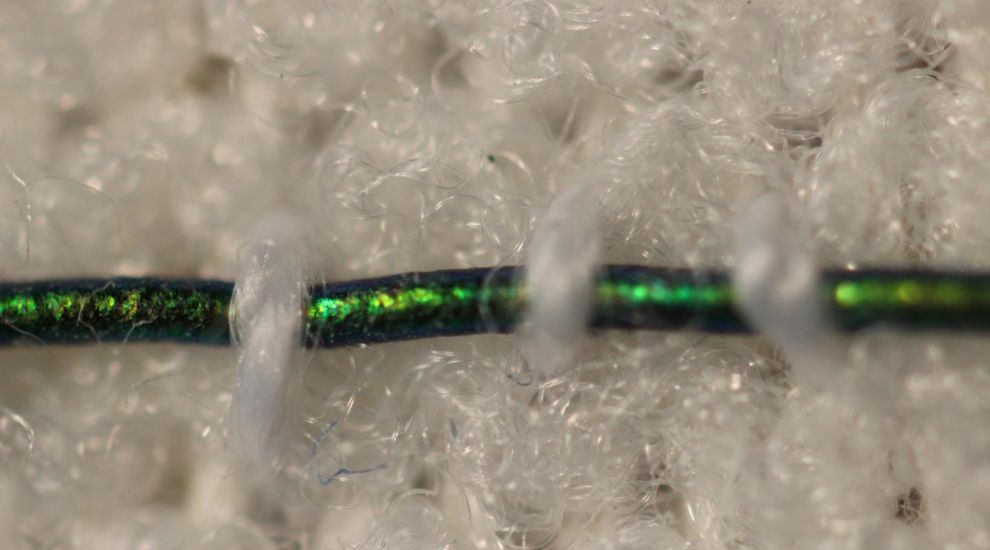

The bandage – which is made of elasticated fabric that allows it to expand – contains pressure-sensing fibres designed to reflect different wavelengths of light.

Compression bandages are used to treat medical issues such as venous ulcers and can help stimulate blood flow, but there is no way of knowing if the pressure being applied is optimal for the specific condition.

Engineers at MIT hope their colour-changing fibres that help solve this problem.

Dr Mathias Kolle, assistant professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, said: “Getting the pressure right is critical in treating many medical conditions including venous ulcers, which affect several hundred thousand patients in the US each year.

“These fibres can provide information about the pressure that the bandage exerts.

“We can design them so that for a specific desired pressure, the fibres reflect an easily distinguished colour.”

The fibres are made from ultrathin rubber material, with layers rolled up to form a jelly-like structure.

Each layer is designed to reflect specific wavelengths of light so when the bandage is stretched, the layers thin out to reflect different colours at different pressure levels – a phenomenon described by the scientists as “optical interference”.

Optical interference is what produces colourful swirls in oily puddles and soap bubbles and gives peacocks and butterflies their dazzling shades.

Joseph Sandt, of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the study’s first author, said: “Structural colour is really neat, because you can get brighter, stronger colours than with inks or dyes just by using particular arrangements of transparent materials.

“These colours persist as long as the structure is maintained.”

The researchers are now looking for ways to scale up the fibre fabrication process.

Dr Kolle said: “Currently, the fibres are costly, mostly because of the labour that goes into making them.

“The materials themselves are not worth much. If we could reel out kilometres of these fibres with relatively little work, then they would be dirt cheap.”

The research is published in the journal Advanced Materials.